Interaction Team

In 1949, two years after gaining independence, Pakistan was still in the process of establishing a cohesive national identity and laying the foundations of a stable state. The country faced numerous challenges in terms of political structure, economic stability, and national integration, yet displayed remarkable resilience and determination.

In the economic domain, Pakistan confronted an array of challenges, including a lack of industrial infrastructure and resources, and struggled to support its burgeoning population. Recognizing these limitations, Pakistan initiated policies to bolster agriculture, which was then the mainstay of the economy. Efforts were made to stabilize trade relations, especially in exporting raw jute to the international market. Additionally, Pakistan reached out to international partners for financial and technical assistance.

The diplomatic landscape was another key focus. Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan’s visit to the United States in May 1949 marked Pakistan’s first official step toward fostering strategic relations with a major global power. The U.S. offered economic aid and pledged support, establishing a long-term alliance that would shape Pakistan’s foreign policy trajectory. This visit also underscored Pakistan’s pivot toward the Western bloc amidst rising Cold War tensions.

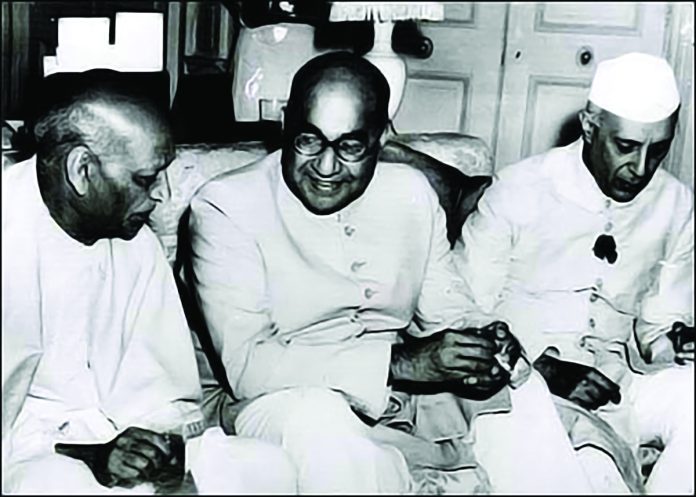

In 1950, Pakistan emphasized diplomacy and building bridges, both domestically and internationally. On April 8, 1950, Pakistan and India signed the Liaquat-Nehru Pact, or the Inter-Dominion Agreement, to protect the rights of religious minorities in both nations. Communal violence in Bengal and Punjab had persisted since Partition, posing a risk to stability. This agreement, which guaranteed security and fair treatment to minorities in both countries, was a diplomatic victory for Liaquat Ali Khan, strengthening Pakistan’s image as a responsible and inclusive state. It reassured minorities within Pakistan and reaffirmed the state’s commitment to communal harmony.

On the domestic front, Pakistan focused on economic stability and self-sufficiency. Karachi, the capital, witnessed rapid development as the government invested in creating a commercial infrastructure that could handle the demands of a growing economy. The First Five-Year Plan was drafted with the aim of transforming Pakistan from an agrarian society into an industrial one. Key industries, including textiles, cement, and food processing, received government incentives and loans to encourage growth. The government encouraged private enterprises to reduce their dependency on imports, thereby fostering a sustainable local economy.

The banking sector was also given importance in 1950. New banking policies were implemented to streamline financial services, facilitating easier access to credit for businesses and individuals. The establishment of financial institutions set the stage for future industrialization and investment.

Internationally, Pakistan’s relations with China began to strengthen, leading to the establishment of formal diplomatic ties. Pakistan also engaged in discussions with Middle Eastern and Southeast Asian nations, promoting a vision of Muslim solidarity. This early outreach laid the foundation for alliances that would evolve over the coming decades.

In 1951, Pakistan continued its efforts to expand agricultural productivity. The government launched initiatives to modernize farming practices, improve irrigation, and distribute land to boost agricultural yields. The focus on agriculture aligned with Pakistan’s aim to achieve food security and support rural communities, which formed a significant part of the population.

Yet, 1951 is most often remembered for the tragic assassination of Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan. On October 16, 1951, while addressing a public gathering in Rawalpindi, Liaquat Ali Khan was fatally shot. His martyrdom was a monumental loss for Pakistan, as he was one of the principal architects of the nation’s policies and a unifying figure. This assassination created a leadership vacuum and stirred widespread sorrow and uncertainty. Nevertheless, Khawaja Nazimuddin, then Governor-General, stepped up to take on the role of Prime Minister, providing a sense of continuity and stability during a turbulent period.

In response to this tragedy, Pakistan’s leaders rallied to honor Liaquat Ali Khan’s vision. There was an increased focus on establishing political order and maintaining the trajectory of development initiatives he had championed.

In 1952, Pakistan faced challenges in managing the cultural and linguistic diversity within its borders. The Language Movement in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) highlighted the need for recognition of local identities. Tensions escalated when the government attempted to impose Urdu as the sole national language, which was seen as unfair by the Bengali-speaking majority in East Pakistan.

On February 21, 1952, students and activists in Dhaka organized protests demanding the recognition of Bengali as an official language. The protests turned violent, resulting in the deaths of several students, a tragedy that deepened resentment and fueled the movement for linguistic rights. This event became a pivotal moment in Pakistan’s history, eventually recognized as International Mother Language Day by UNESCO. The government later acknowledged Bengali as an official language in 1956, marking a significant concession to cultural diversity.

Amidst these challenges, Pakistan joined the International Islamic Economic Conference, an effort to strengthen ties among Muslim nations. This diplomatic endeavor reinforced Pakistan’s commitment to Muslim unity and showcased its aspirations on the global stage.

Domestically, Pakistan pursued its economic agenda by advancing its industrial policies. Karachi saw further investment in manufacturing and infrastructure, which not only created jobs but also bolstered the country’s economic resilience. Efforts to develop the jute industry in East Pakistan were also undertaken, with plans to enhance jute processing and export capabilities. This helped the eastern region’s economy and showed Pakistan’s efforts to bridge economic disparities between its two wings.

The 1953 Tehreek-e-Khatm-e-Nabuwwat movement was unforgettable and impactful against the Ahmadiyya (Qadyani) movement. The unfortunate tragic deaths of between 200 and 2,000 protestors made it violent. As the situation spiraled beyond police control, Governor-General Malik Ghulam Muhammad placed the city under martial law on March 6, transferring administrative authority to the army led by Lieutenant General Azam Khan.

Historically, the Ahmadiyya Community had supported the Pakistan Movement and, after independence in 1947, flourished in various high-ranking government and military roles. Their influence remained weighty, particularly due to their support for secularism, which acted as a counterbalance to Majlis-e-Ahrar-ul-Islam. However, on January 21, 1953, a delegation of ulama from the Majlis-i-Amal (Council of Action), formed by the All-Pakistan Muslim Parties Convention in Karachi, presented an ultimatum to the Prime Minister of Pakistan. They demanded the removal of Ahmadis from top government offices, the dismissal of Zafarullah Khan from the foreign ministry, and a formal declaration of Ahmadis as non-Muslims. When these demands were rejected, violent disturbances ensued.

Following the declaration of martial law on March 6, the military worked to restore order under the leadership of Azam Khan, with Lahore returning to calm within 70 days. During this period, Maulana Abdul Sattar Khan Niazi, Secretary General of the Awami Muslim League, was arrested and sentenced to death, though his sentence was later commuted. Politically, the events had far-reaching consequences: Ghulam Muhammad dismissed Punjab’s Chief Minister, Mian Mumtaz Daultana, on March 24, alleging that he had exploited religious sentiments for political gain. Shortly after, on April 17, Ghulam Muhammad dismissed Prime Minister Khwaja Nazimuddin and his entire federal cabinet, appointing Muhammad Ali Bogra (then Pakistan’s ambassador to the United States) as the new Prime Minister. Several leaders, including Abul Ala Maududi, Mawlana Amin Hussain Islahi, Malik Nasrullah Khan Azeez, Syed Naqiullah, Chaudhry Muhammad Akbar Sialkoti, and Mian Tufail Mohammed, were arrested in March 1953 and sent to Lahore Central Jail. (Continue…)