Dr. Samreen Bari Amir

According to Johan Galtung, the media has a magic wand that allows it to decide how and when to report on a particular incident. whether to treat it as a diplomatic matter, a crisis, or a war. Galtung defined peace journalism as contextual, evidence-based reporting that demonstrates the effects of war on human emotions, human lives, cost of war, while war journalism depicts feelings through the US vs. THEM narrative. Peace journalism primarily centers on communication and diplomacy.

Based on a number of case studies, we may conclude that the media shapes conflicts and is now a weapon of war. A sharper weapon is more powerful, more lethal, and its effects last for a very long time. Consider World War I, when Japan was depicted by the Western media as a center of evil. The media depicted Japan as a vicious foe and implied that Japanese people should be punished.

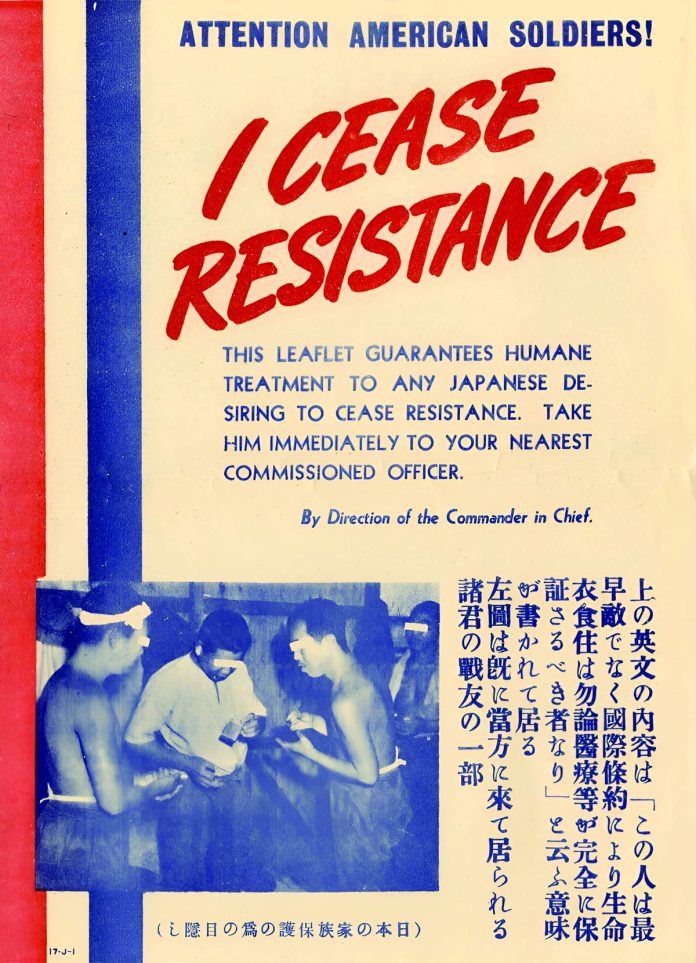

Racist and demeaning imagery was frequently employed in the media. The war was presented as a conflict between good and evil in posters, movies, newspapers, and radio shows, which supported brutal military tactics like the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The U.S. government and Hollywood collaborated to demonize the Japanese and foster patriotism by referring to them as “Japs” and displaying exaggerated characteristics. Because of its wider audience, radio was a vital medium in both Japan and its allies to inform the public about army readiness, war updates, and war bonds. It was also utilized to foster national unity and to instill nationalistic values in the public sphere.

Newsreels and newspapers depicted valiant American soldiers and ruthless Japanese acts (such as the Bataan Death March), inciting rage and determination. In order to demoralize Japanese soldiers and citizens and encourage surrender, the US government even employed leaflet drops to disparage Japanese people and the government through Voice of America and other broadcasts. Although it was mostly unsuccessful, Japan also attempted to lower the morale of American soldiers through the media, such as Radio Tokyo and its “Tokyo Rose” broadcasts. Amazingly, both nations applied because they were terrified of free and fair media. Strict media restriction was a practice shared by the US and Japan. Content pertaining to war was governed by the Office of War Information (OWI) in the United States. Only pro-war messaging was permitted on the radio and in publications in Japan due to the strict government regulations.

The Cold War was a prime example of a media war; it was waged between the US and the USSR on the basis of ideology, through the media, and through an arms race and war preparedness. The global dissemination of ideology, propaganda, and fear was greatly aided by the media. Both American and Soviet media were vying with one another to propagate and advance their own philosophies. American media did more than just portray capitalism and democracy as engines of liberty and wealth. but also depicted socialism as a destroyer of freedom and prosperity, much how Soviet media depicted capitalism as avaricious and exploitative and communism as just and anti-imperialist.

Both superpowers were utilized. Subtly, these world views were promoted through TV series, movies, cartoons, and literature. CNN and the BBC both had a major impact on the Iraq War (2003) by spreading information and influencing public opinion throughout the world before, during, and after the war. CNN is renowned for providing round-the-clock, real-time war news. It provided audiences with a frontline view by embedding journalists with U.S. military troops.

Critics countered that this resulted in a narrative that was biased and focused on the United States. However, BBC Offered more international coverage and occasionally questioned the narratives of the US and UK governments, particularly with regard to the legitimacy of the war and WMDs. CNN frequently repeated the Bush administration’s defense of war (such as Saddam’s WMDs and ties to terrorism), which helped garner support at home in the United States.

More critical broadcasts were broadcast by the BBC, highlighting civilian losses and featuring opposing viewpoints that questioned the justification for war. The BBC’s “sexed-up dossier” report which Journalist Andrew Gilligan asserted in 2003 that the UK government gave false information about Iraq’s WMDs. The Hutton Inquiry, the resignation of BBC executives, and a significant discussion about media-government ties resulted from this.

CNN came under fire for neglecting to challenge official narratives and for being unduly supportive of American military objectives, particularly in the early phases of the conflict. Embedded journalists were deployed by the BBC and CNN networks, providing access but limiting independent verification. Critics contend that this encouraged prejudice and hindered the media’s ability to openly report on the situation on the ground. Because of their worldwide viewership, the BBC and CNN’s stories influenced opinions on the war that went well beyond the United Kingdom and the United States, impacting discussions and responses around the world.

During India-Pakistan conflicts (e.g., Kargil 1999, Mumbai 2008, Uri 2016, Pulwama-Balakot 2019), media on both sides often act as extensions of national security narratives. Emphasizes military preparedness, unity, and defensive posture. Highlights aggression, human rights violations, or false flag operations. It airs patriotic songs, panel shows with military analysts, and sensational headlines. Often repeats the government’s statements without critical analysis.

As of 2024, India has 393 private satellite news television channels, according to the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. These channels operate in multiple languages, including Hindi, English, Tamil, Telugu, Bengali, Marathi, and others. In addition to these television channels, India hosts over 3,700 digital news publishers, highlighting the significant presence of online news media in the country. Overall, India has more than 900 satellite TV channels across various genres, with news channels constituting a substantial segment.

India, despite having a vast media landscape with hundreds of news channels, is increasingly plagued by extreme jingoism and an apparent lack of regulatory control over its media outlets. The reality remains that, much like a bullet once fired or words once spoken, the damage caused by irresponsible reporting cannot be undone.

This places a serious ethical obligation on the media to act with maturity and restraint. During the recent tensions between India and Pakistan, many Indian news channels acted recklessly, fueling public sentiment and pressuring the government toward aggression. In doing so, they played a dangerous and provocative role, arguably becoming active participants in escalating hostilities. Notably, the Modi government has been criticized for leveraging these media platforms to promote war hysteria and inflame anti-Pakistan narratives for political gain.

It is a well-observed fact that during times of heightened tension, particularly in conflicts like that of 2025, sections of the Indian media assumed a role more akin to a war instigator than a responsible mediator. Instead of promoting calm and reasoned discourse, many outlets amplified aggressive narratives, sidelined moderate voices, and sensationalized military actions.

In such sensitive times, the role of the media should not be to inflame public emotions or pressure governments toward conflict, but to uphold journalistic ethics by promoting facts, critical analysis, and dialogue. What’s urgently needed is a media landscape that elevates voices of reason, encourages cross-border understanding, and creates space for peaceful negotiation rather than perpetuating division and hostility.

The author is Assistant Professor and HoD of IR Department at DHA Suffa University Karachi.