By Xie Chao

Last week, rampant violence in Ahmedabad, the capital city of Gujarat has killed at least 10 people, a tragic event that reminds us of the same state in 2002, when a succession of inter-communal riots caused hundreds of casualties.

The Patidar, a large local traditionally agricultural caste, are rallying en masse for a higher quota of government jobs and college places reserved for the “scheduled castes,” traditionally disadvantaged communities. The government reacted swiftly, but the rally turned violent due to overt police action, and in the end curfews were imposed and troops sent in.

In 2002, Narendra Modi, currently Indian prime minister and then the chief minister of Gujarat, was widely criticized for his mishandling of the situation after government inaction let violence against Muslims go unchecked.

If police inaction caused widespread violence in 2002, it was the excessive use of police force that plunged the state back into violence 13 years later.

Amid waves of criticism of the heavy-handed police reaction, Modi came out to endorse the local police and cleared further responsibility for more government attention to communal issues by saying that India needs development.

In a speech calling for public calm, he stressed that development is “the only solution of all problems.” Needless to say, such rhetoric failed to console the state’s minorities, again. Will development solve all problems? Can social problems be solved if the economy simply grows? Obviously, the answer is more complicated than such a simple solution of development.

Economic development won’t solve all problems. The fact is that fast-growing Indian states cannot save themselves from communal violence, let alone those which are struggling in poverty.

Gujarat, after decades of fast development, is now ranked as one of the most prosperous states in India, but thenightmare of communal confrontation continues to haunt it.

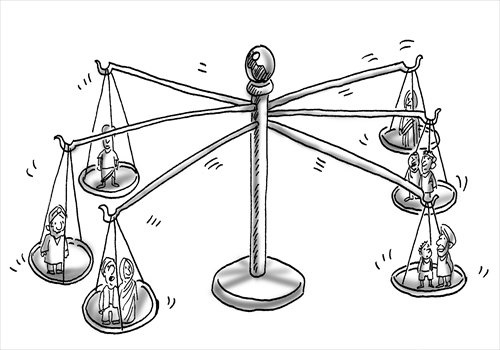

Economic development makes certain problems more prominent. Recent violence in Gujarat has shown that the issue of communal inequality becomes more salient when groups are receiving uneven benefits. What’s disturbing in this case is that even those who are supposed to have received a larger share of the pie are not comforted.

About a fifth of Gujarat’s population, the Patidar as a caste are among the richest in the state. Historically, they were landowners and farmers and now constitute a visible presence in Gujarat’s economy. National brands such as Nirma detergents and Zydus Cadila pharmaceuticals, and 70 percent of the US motel industry, are in their hands. But they are now standing among the fiercest in fighting for reserved places.

Besides the Patidar in Gujarat, other communities in other parts of the country are asking to be counted as “backward” groups in need of help. For example Jats in Haryana, and Marathas, Muslims and Dhangars in Maharashtra are pressing the government for a decision on their reservation requests.

While Modi and some others believe that the 2014 elections were about the economy alone, caste politics still prevails.The current communal upheavals also call into question the image of a prosperous and vibrant Gujarat that Modi tried to sell to the world.

If the Gujarat model was so successful and so transformative, how could this caste-centric mobilization erupt and end so violently? Why should other states buy into the rhetoric?

Modi has branded India as one of the fastest growing economies after revising GDP measurement, and he has also taken a strong presence on the international stage. But the Modi momentum is more talk than reality, and it is high time for him to turn more attentions to domestic, to work more on creating jobs and delivering inclusive growth.

Courtesy ‘Global Times’