Interaction Team

Though, in March 1956, Pakistan achieved a historic milestone by enacting its first constitution, but the excitement surrounding the new constitution was short-lived. The leadership failed to navigate the complexities of running a federal parliamentary system. Within months, the country was plunged into political turmoil as a series of prime ministers were either dismissed or forced to resign.

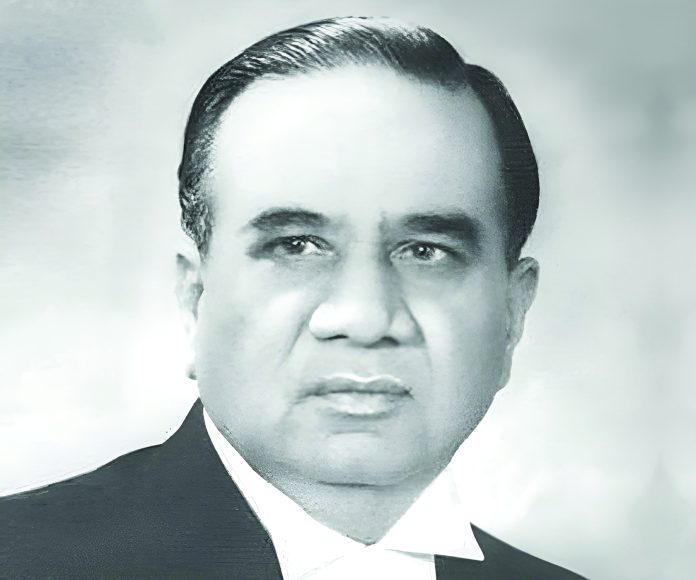

This period saw the rapid turnover of governments, a phenomenon that eroded public trust in the political system. Leaders like Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, who envisioned greater cooperation between East and West Pakistan, faced resistance from entrenched political elites in West Pakistan. His efforts to promote national integration and equitable resource distribution were thwarted, leading to his resignation in 1957. His successors, including Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar and Feroz Khan Noon, also struggled to maintain political stability, often becoming casualties of factionalism and infighting.

The divide between East and West Pakistan deepened during these years. Despite East Pakistan’s larger population, it felt increasingly marginalized in national decision-making. This sense of alienation was further exacerbated by the central government’s inability to address the grievances of East Pakistanis, who felt excluded from the corridors of power.

While the political scene descended into chaos, Pakistan’s foreign policy took a decisive turn towards the West. The country became a key ally of the United States during the Cold War, joining alliances such as SEATO and CENTO. These alliances brought military and economic aid, bolstering Pakistan’s defense capabilities, but they also attracted criticism for aligning too closely with Western powers, potentially compromising the country’s sovereignty. Domestically, the benefits of this foreign aid failed to trickle down to the masses, further fueling discontent.

As the political crisis worsened, the influence of the military and bureaucracy grew. President Iskander Mirza, who had risen to power under the 1956 Constitution, increasingly relied on the military to maintain order and control. This reliance on non-democratic institutions undermined the parliamentary system and set the stage for future military interventions. Mirza’s authoritarian tendencies became evident as he dismissed prime ministers at will, bypassing parliamentary procedures and consolidating his grip on power.

By 1958, the political system had become unsustainable. The endless cycle of political instability, combined with economic mismanagement and regional tensions, created a sense of crisis. In a dramatic move, President Iskander Mirza abrogated the constitution, dissolved the National Assembly, and declared martial law on October 7, 1958. This marked the end of Pakistan’s first attempt at democratic governance.

To enforce martial law, Mirza appointed General Ayub Khan, the Army’s Commander-in-Chief, as the Chief Martial Law Administrator. However, this alliance was short-lived. Within weeks, Ayub Khan forced Mirza into exile on October 27, 1958, accusing him of conspiratorial tendencies, and assumed full control of the country, ushering in the era of military rule.

In 1959, Ayub Khan’s regime embarked on an ambitious path of reform and centralization to cement its hold on power and set the country on a trajectory of economic and administrative transformation. One of the most notable initiatives was the introduction of land reforms aimed at curbing the dominance of large landlords.

These reforms, announced in January 1959, placed a ceiling on land ownership, redistributing approximately 2.5 million acres among landless farmers. While the policy appeared progressive on paper, its impact was diluted by loopholes and strong resistance from influential landowners who managed to avoid many of its provisions.

Concurrently, Ayub’s government launched a vigorous anti-corruption drive, seeking to cleanse the political and bureaucratic landscape. Tribunals were established to investigate and prosecute allegations of malpractice, sending a strong message against the entrenched corruption that had plagued the country. However, this campaign was selective in its implementation, often targeting Ayub’s political rivals more than addressing systemic issues.

In the same year, Ayub introduced a political framework known as the Basic Democracies System. This system aimed to decentralize governance by establishing a network of local councils in rural and urban areas, ostensibly empowering ordinary citizens. However, the system also served as a mechanism for Ayub to consolidate his control.

The Basic Democracies Ordinance created a tiered electoral structure where local council members were indirectly involved in the selection of national leadership, providing Ayub with a tightly managed pathway to secure political legitimacy without the unpredictability of direct elections. Economic development became a cornerstone of Ayub’s agenda, with a particular emphasis on industrialization and infrastructure. The government actively encouraged private investment and sought foreign aid, particularly from the United States, which saw Pakistan as a key ally in the Cold War. Membership in alliances such as SEATO and CENTO further strengthened this partnership, funneling economic and military aid into the country. To institutionalize economic planning, Ayub’s administration established the Planning Commission, laying the groundwork for long-term growth strategies that would guide Pakistan’s industrial and agricultural development in the years to come.

(Continue)